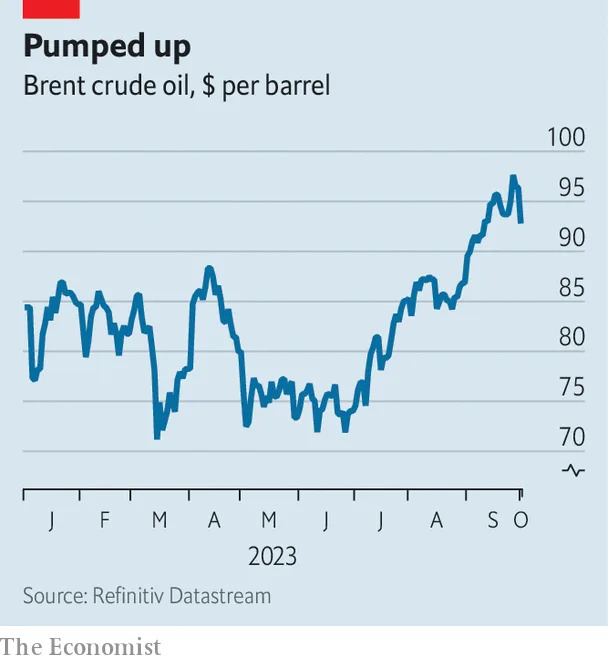

The Economist, via Yahoo News: In the first half of the year, Saudi Arabia and its allies in the Organisation of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) appeared to be digging themselves into an ever-deeper hole. Crude prices, which exceeded $125 a barrel for much of June last year, languished below $85. To arrest the slide, which had been caused by falling demand owing to weak growth in China and rising interest rates elsewhere, OPEC kept extending the output cuts they had first announced last October. Then prices fell to $72 in June. The cartel was selling less and less oil, for less and less money.

But OPEC’s run of bad luck came to an end in July, when Saudi Arabia decided on an extra output cut of 1m barrels a day (b/d)—equivalent to 1% of global demand—and said it would extend the cut into August. Since then, Saudi Arabia and Russia have extended cuts to the end of the year, a course they are likely to stay on at an OPEC meeting on October 4th. At the same time, investors, who had expected the global economy to enter recession this year, took heart from signs that inflation in America had slowed, forecasting the end of rising rates and maybe even an economic “soft landing”. The combination has pushed up oil prices by 30%, to more than $90 a barrel.

What happens next? Traders are blowing hot and cold. Last week prices passed $97; now they are under $92. Amid such volatility, pundits are debating if the rally is just starting or petering out. The bears predict a level below $90 by Christmas. The Bulls foresee triple digits before then. The stakes are high, and not just for OPEC: dearer oil will push up inflation, which may force central banks to keep policy tight, and deal a blow to the global economy.

The bulls base their case on the surprising resilience of oil demand. Economic and literal headwinds, in the form of a mighty typhoon, did not deter Chinese tourists and businessfolk from travelling a record amount this summer, boosting demand for petrol and jet fuel. American travel, which peaks on the Labour Day weekend in early September, has remained strong. Overall, it seems the latest price rise is not dampening oil consumption. Jorge León of Rystad Energy, a consultancy, estimates that such demand destruction would only happen at $110-115 a barrel.

Bulls also see that supply cuts are filling producers’ pockets, opening the possibility they may be extended again. Despite lower export volumes, Saudi Arabia’s revenues could be $30m a day higher this quarter than last, a jump of 6%, reckons Energy Aspects, a consultancy. Russia’s revenues are also up. Both can take comfort from the fact that, unlike in the late 2010s, when OPEC and Russia first teamed up to cut supply, American shale drillers are not filling the gap. Production is rising for the moment, but they are shutting wells, squeezed by higher costs. Rig numbers are down 20% from last November.

This week’s price decline reflects “profit-taking” by traders, bulls argue. They point to a forecast 1.5-2m b/d supply deficit for the year as a whole, most of which is due to materialise in the last quarter, as record production by non-OPEC countries, such as Brazil and Guyana, is finally outpaced by the cartel’s cuts. This will force users to dig further into stocks. Inventories at Cushing, a crucial oil hub in Oklahoma, have declined to their lowest levels in 14 months.

Yet the bears see things differently. They believe that the recovery in China’s oil demand has already happened, even if that of the economy at large is far from complete, since lockdowns had an outsize effect on activities, such as those involving transport, that are thirsty for oil. JPMorgan Chase, a bank, projects that Chinese demand will be flat for the rest of the year. Moreover, China imported record volumes of crude in the first eight months of the year, a lot of which it stockpiled to be refined later. History suggests that it will pause purchases if prices rise further.

Worrying signs are also emerging from America. Pressure from high oil prices is reaching “core” inflation, which excludes food and energy costs, as firms in other sectors, starting with transport, raise prices to compensate. The Cleveland branch of the Federal Reserve’s “Nowcast”, which uses oil and petrol prices as inputs, projects it will edge up to 4.19% year on year this month, from 4.17% in September. Analysts expect it to remain sticky at 3% in the longer run. Thus the Fed is more likely to keep rates higher for longer, dampening America’s economy and pushing up the dollar, which makes oil dearer for everyone else.

Bears also dismiss the depletion of stocks at Cushing, pointing out that, as America became an exporter of crude in the 2010s, storage activity shifted to the Gulf Coast instead. Crude inventories elsewhere have not diminished as fast. Global stocks remain above the five-year average. Although bears agree that these stocks will be drawn down in the forthcoming quarter, they expect the market deficit to shrink fast next year, when non-OPEC production growth should cover most of the rise in demand. Kpler, a data firm, projects a surplus for the first few months of 2024.

The bulls look to have a case in the short run, but the bears will have the upper hand by next year. The market is likely to be tight until January. Surprise economic data could cause swings of $5-10 a barrel, buoying prices above $100. Yet in 2024, the lagging impact of high rates will subdue demand as new production arrives, calming prices. A gradual descent may follow.

There is still an unknown. Although Saudi Arabia has given hints that it is worried about the economic prospects of its Asian and European customers, lower benchmark prices may nonetheless push it to bigger production cuts. If there is a glut of supply, such cuts may not be enough to push up prices. Yet they will prevent the rebuilding of stocks, which normally happens during downturns. That would set the stage for the next oil-price thriller.

© 2023 The Economist Newspaper Limited. All rights reserved.

From The Economist, published under licence. The original content can be found at https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2023/10/03/will-oil-hit-100-a-barrel