Story from Hart Energy, via Yahoo News. The roots of oil and gas’ looming talent challenge began with the end of the World War II. Returning GIs anxious to start a new life began getting married and having kids, lots of kids. An estimated 78 million baby boomers were born between 1946 and 1964. They began retiring in 2011 and most will be done by 2029.

Oil and gas had managed to put off the so-called “Great Crew Change” for a time because equity values were “crushed” between 2014 and 2020, said Les Csorba, partner in the Houston office of executive search firm Heidrick & Struggles. But no longer. Oil and gas is now one of the best performing equity classes, and rising stock prices means the sector is seeing more retirements, Csorba said.

To be sure, the pandemic has also played a role, accelerating the pace of retirements for older workers.

“Companies are worried about retirements over the next year to 18 months across the C-suite,” Csorba told Hart Energy. Succession planning is becoming a real issue as oil and gas enterprises wrestle with how to replace experienced senior managers with younger, less experienced workers.

It’s for that reason that Csorba, along with his colleague Clayton Spears, produced the recent report “The next energy crisis? Talent.”

Chuck Yates. (Source: Hart Energy)

Replacing those retirees is made more complicated by factors specific to oil and gas.

“There’s a huge gap in middle management,” said Csorba. Previous downturns forced layoffs that pushed talent from the sector, as well as growing anti-hydrocarbon rhetoric that has tamped down interest in oil and gas careers.

The true scale of the problem has been masked to a degree by private-equity investment in the sector between 1997 and 2017, said Chuck Yates, a former managing partner at Kayne Anderson Capital Advisors. Such investment created opportunities for young executives to gain experience as part of a startup management team and create the potential for significant rewards, he said.

Private equity’s decreased prevalence shrinks those opportunities for young talent, Yates told Hart Energy. Meanwhile the current state of the market scares off potential new entrants because it creates “unlimited downside and limited upside,” he said.

Yates himself lost his job at Kayne Anderson in 2020 and is now a self-proclaimed “social media influencer” through his podcast, “Chuck Yates Needs a Job.”

Start at the top

The scale of the oil and gas talent problem is so large that it demands board-level involvement, similar to ESG risks, said Csorba. Companies might consider creating reports to demonstrate the sustainability of their talent pipeline.

“I would argue that leadership and succession planning and talent is also a material risk to the longevity of a business,” said Csorba.

Csorba and colleague Spears suggests companies should report on: efforts to develop, recruit and retain the next generation of leaders; leadership initiatives, academies, coaching and mentoring programs; C-level executives of the future programs; and whether external leaders are being recruited to continually reinvigorate leadership, innovation and diversity of experience.

Csorba said chief human resources officers (CHROs) may play a strategic role in such efforts. Just as a CFO and head of audit work closely with audit committee chairs, CHROs should more actively report to and participate in nominating and governance committee meetings on boards and be accountable alongside the CEO for the company’s leadership strategy.

Such executives should probably be reporting quarterly to the board of directors and be more involved in executive compensation. The board’s key responsibility, after all, is to hire and fire the CEO, he said.

Boards should hold management teams more accountable for rigorous talent acquisition and leadership development programs, Csorba and Spears said, and maybe consider making this metric a part of executive compensation plans.

“Boards really ought to be focused on that,” said Yates, adding that talent management is “business 101.”

The directors’ role is not necessarily to tell companies what to do, but rather to provide guidance on what not to do, he said. They should also ask questions. The board should get answers to basic questions such as the company’s recruiting plan, how many people are needed, the average cost when an employee leaves and what happens if something were to occur to senior management, Yates said.

Yates sits on the board of directors of Black Mountain Acquisition Corp., a Fort Worth, Texas-based special purpose acquisition company focused on opportunities in the energy industry in North America led by CEO Rhett Bennett. Yates is also on the advisory board of Montrose Lane, a venture capital firm focused on digital solutions for the energy industry, and a “big brother” to the founders of Digital Wildcatters, a social media company focused on energy.

READ NEXT: Future Of Oil And Gas Industry Uncertain

Needs assessment

When considering how to develop future leaders, Csorba and Spears said that energy executives must move away from being specialists and look to become more like decathletes, who are proficient in many areas. Those include financial performance, investor confidence, innovation, social or people or safety leadership, environmental stewardship, reputation and risk and resilience.

Executives are shouldering new demands that didn’t exist previously. Expectations include increased disclosure and transparency regarding ESG factors to investors and analysts, more aggressive shareholder activist campaigns and the ever-rising importance of technology.

Technology holds a stark duality, Csorba said. Leveraging big data offers great potential, for instance, in aiding decision-making on proper well spacing or other operational matters.

But greater reliance on technology exposes companies to cybersecurity risks, as the Colonial Pipeline ransomware hack demonstrated. Future leaders will need to balance that risk/reward. For that reason, some companies look to have generational diversity within executive teams and boards to enhance their digital expertise.

Despite the technical sophistication of oil and gas when it comes to applying technology to solving large problems, such as using 3D seismic to make massive new oil finds, the industry does less well in using technology to run more efficient businesses, Yates said. He points to the large amount of written ledgers and actual paperwork in the sector that does not help when recruiting younger talent who grew up using apps on their phone.

Other applications of technology likely going underutilized in oil and gas include those focused on employee health and mental wellbeing, said Yates.

“If I have employees that are at the top of their game, particularly with mental health, I’m going to get better performance,” he said. Other sectors have invested significant effort into using technology to deliver those offerings, Yates said.

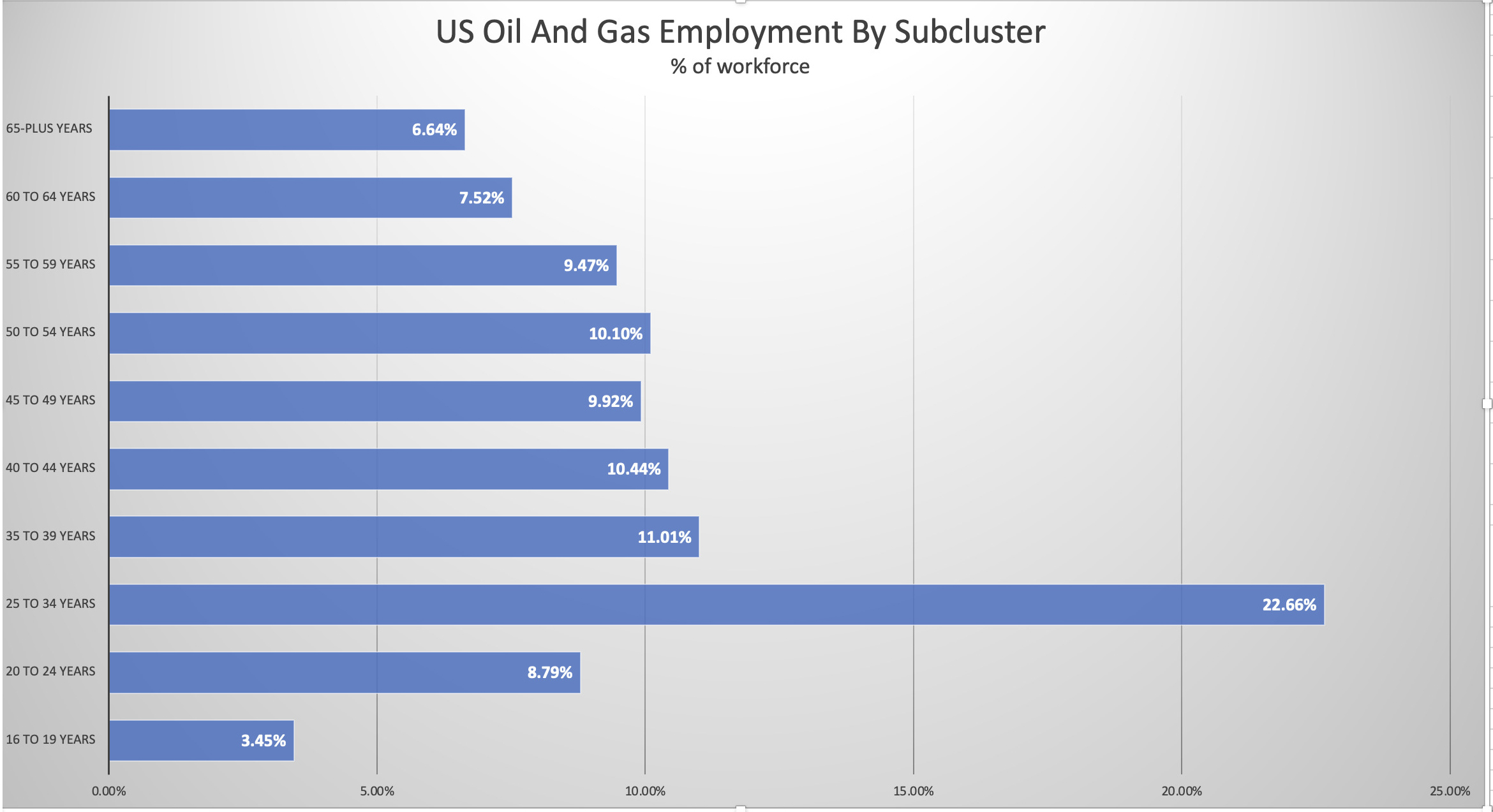

US Oil and Gas Employment by Age Group. (Source: Bureau of Labor and Statistics)

Think outside the sandbox

Not all the hurdles oil and gas companies face are negative.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the industry meets more than 81% of current global energy demand and will only see moderate declines in the future. Hydrocarbon market share is only expected to drop to 78% over the next 20 years as overall worldwide energy demand is expected to grow by as much as 50% by 2050, IEA estimates show.

That means oil and gas companies must not only develop leaders who can meet existing requirements efficiently and profitably but also do so in an environment of rising demand. Csorba and Spears said that future leaders may benefit from looking outside the oil and gas sector for potential solutions in related industries.

Specifically, they see the potential for cross-pollination between oil and gas and renewables. They share much in common, not the least of which is powering all other industries and contributing to the flourishing of human civilization.

Renewables is one of the fastest growing portions of the energy sector, averaging 15% CAGR between 2015 and 2020, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. Although renewables are often held up in opposition to oil and gas, the truth is addressing the energy supply challenge will require maximum effort by both sectors, Csorba and Spears said.

Renewables’ fast growth has created a need to “get creative” to get bodies in the door, said Spears, who focuses on the sector for Heidrick & Struggles. One approach is to appeal to the mission-driven concerns of younger generations by focusing on sustainability and benefits to the environment to attract new leaders. The renewables sector leads with their mission, not profits, he said.

In many ways, the oil and gas industry has “stuck its head in the sand for 50 years” when it comes to marketing its value to the world, said Yates. Part of the problem he attributed to the fact that oil and gas does not have a culture of marketing because it sells a commodity. Nevertheless, the sector needs to demonstrate its thought leadership and better control its narrative, Yates said.

“Cleaner and greener” is important to oil and gas to fill the pipeline for talent, Spears said. Large upstream players have already begun the pivot by highlighting their investments in new energy segments, he noted.

Oil and gas executives need diverse skill set. (Source: Shutterstock)

Last March, Exxon Mobil Corp. announced plans to build a 1 Bcf/d hydrogen production plant in Baytown, Texas, as well as carbon capture facilities to handle up to 10 million metric tons (MMmt) of CO₂ per year. In December 2022, Chevron Corp. announced a joint venture with Baseload Capital to develop geothermal projects in the U.S. Last March, Occidental Petroleum Corp. disclosed efforts to build 70 carbon capture facilities by 2035 to remove 1 MMmt of CO₂ per year directly from the air.

Csorba also pointed out oil and gas services companies such as National Oilwell Varco and Kirby Corp. are announcing plans to provide support for the burgeoning offshore wind power industry.

While oil and gas can learn from renewables, it has much to offer itself from an operational perspective, particularly in terms of operational, regulatory and safety matters, said Csorba. Those are important, as renewables have a very large scalability challenge ahead of it, he said.

Closer collaboration stands to benefit both segments, said Yates.

In the future, Yates expects companies to focus more on delivering a diversified slate of energy offerings. That means companies will be less focused on energy type and more concentrated on geographic position. For instance, West Texas not only has world-class oil and gas reserves but also generates a record amount of solar and wind power.

Regardless of the particulars, the large-scale trends are clear. Oil and gas, along with the rest of the energy sector, has a bright outlook but must take steps today to avoid creating a crisis in the future.

Story Credit: Mark Druskoff, Contributing Editor, Hart Energy Staff