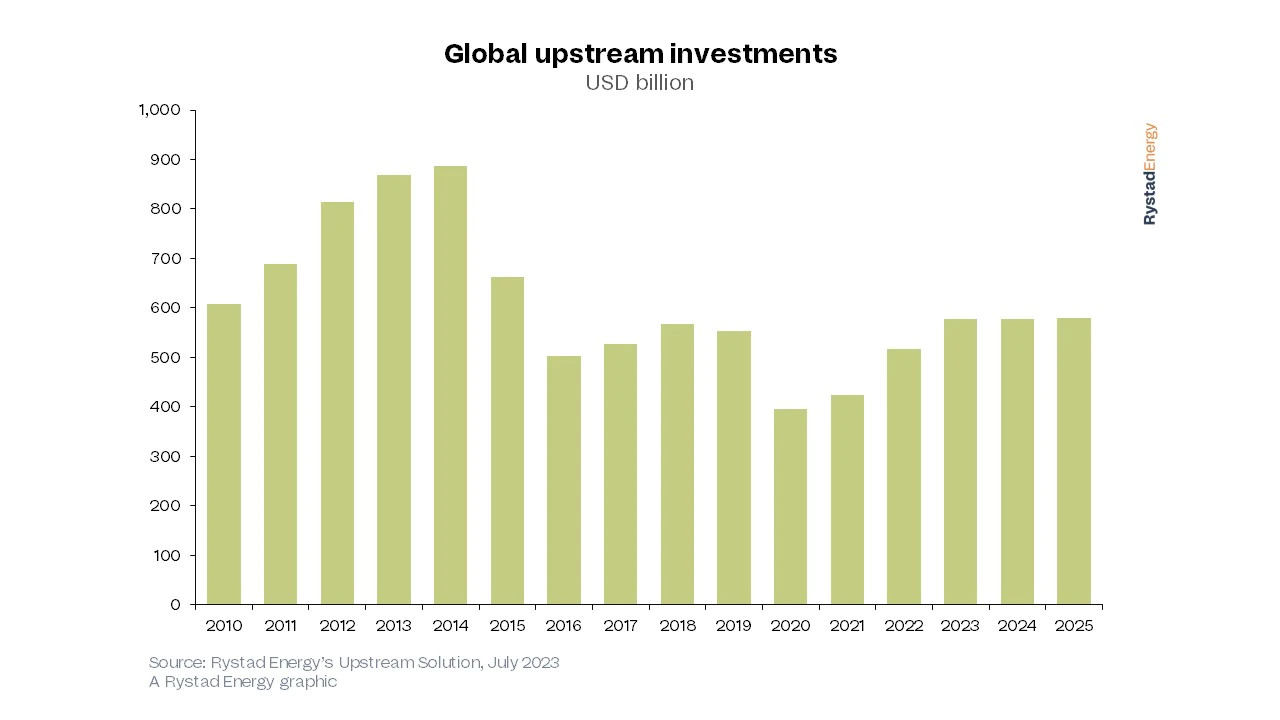

Story By Chris Matthews |Hart Energy| Fears of underinvesting in oil and gas are way off the mark, according to a new Rystad Energy report. The consultancy says efficiency and productivity gains, lower oil production costs, and a sharper focus on more mature wells and the highest-producing wells are handily making up for a more than 40% drop in global upstream investment since 2014.

Contrary to popular opinion, the world is investing appropriate amounts of money in fossil fuel production to satisfy demand. Cost savings mean operators can produce the same amount of oil at a lower cost, and we don’t foresee an oil supply crisis due to underinvestment on the immediate horizon. ~Espen Erlingsen, head of upstream research, Rystad Energy

That is the conclusion Rystad has turned out in an analysis at odds with the dominant view within the oil and gas industry. Analysts and E&P companies have long said chronic underinvestment could have serious consequences. Hess Corp. CEO John Hess has been outspoken on the lack of capital investment in the sector, which he has said could be one of the “greatest challenges the world has.”

But Rystad, a Norwegian energy research company, says they are all looking at the numbers wrong.

“We don’t think the total oil and gas investment numbers are telling the full story. Efficiency gains, productivity gains, and portfolio effects have made the upstream industry much more efficient, and we get much more out of every dollar spent now compared to earlier,” Espen Erlingsen, head of upstream research at Rystad told Hart Energy. “We predict that the current activity level can keep up with demand.”

The analysis found that the industry is hitting the same production levels reached during the robust years of 2010 to 2014 — but at much lower costs. Rystad analyzed the development of oil prices for different supply segments and found production costs have come down 20% to 30%, resulting in more activity for every dollar spent.

The number of new wells worldwide drilled peaked at about 88,000 in 2014 when global upstream investment reached its highest point at nearly $900 billion. The new well count dropped for a few years and then grew steadily from 2016 until the pandemic in 2019, according to Rystad.

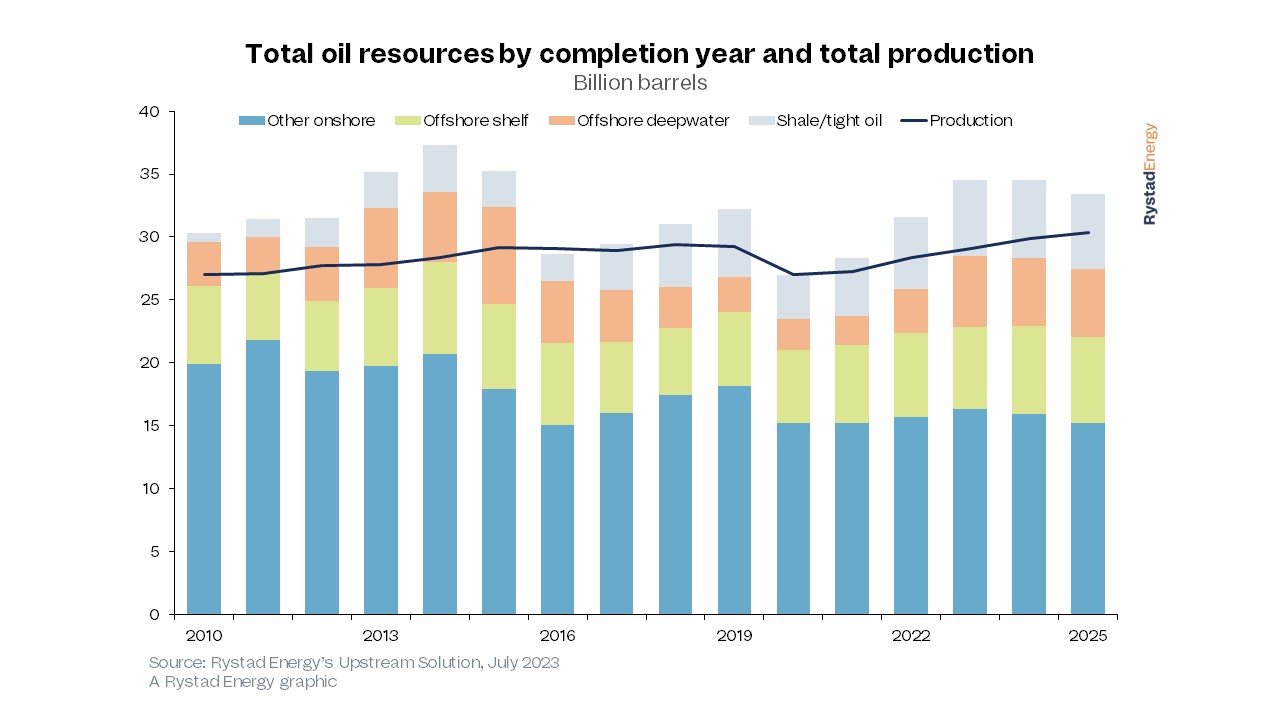

Now the world has fewer new wells, but they produce more efficiently. There were about 55,000 new wells in 2022—a decrease of about 35% from 2014. The wells drilled in 2014 have a total production potential of 37 Bbbl of oil over a lifespan of about 30 years.

The wells drilled in 2022 are fewer in number but produce at nearly as great a capacity, Rystad said. The firm estimates they have nearly 32 Bbbl of oil. That productivity is being achieved with only 60% of the capital investment the industry had in 2014, and productivity may reach 35 Bbbl by the end of 2023, according to the analysis.

“It is not sufficient only to look at investments, you also need to understand how we are developing resources,” Erlingsen said.

When fewer wells were drilled, the focus on more productive wells sharpened, according to Rystad.

“Our modeling and analysis tell a different story” about the industry’s need for capital, Rystad said in a statement with its analysis. “The industry can do the same as before, but at a much lower cost.”

In June, the International Energy Agency said that oil demand will slow significantly by 2028, and the U.S. Energy Information Agency forecasts lower global oil production through 2024.