I have argued in a succession of OilPrice articles, here, here, and here, that the era of rapid growth in shale production output was coming to an end. Until recently it was a little difficult to see as production has ramped +/- a million barrels a day from 2020 lows. Still, there has been a disconnect between a couple of reports put out by the Energy Information Agency-EIA, that are used to track U.S. domestic output. I refer to the EIA-Drilling Productivity Report-DPR, issued monthly, usually at the beginning of week-3, and the EIA-914, a monthly report published on the last day of the month.

The DPR projects the present month and the next month to come, making it a forecast of production based on industry reports and governmental and state agency filings. The 914 is considered to offer more accurate data as it shows production two months in arrears. Each report has its utility and is the best compilation of data that can be had from public sources.

The graph above charts data released on the Permian basin in these two reports and clearly shows a deflection between them of up to several hundred thousand BOPD. The gap is likely primarily influenced by the DPR which also tracks Drilled but Uncompleted Wells-DUCs that are withdrawn from the operator’s inventory to help maintain production and optimize field production. Beginning in the middle of 2021 and continuing to January of 2022, there was a massive drawdown in DUC inventory that has helped to skew production higher.

The graph above shows the productivity decline in the daily output of new shale wells, divided by the number of rigs operating over the last year and a half. Some of this is noise from the increase in the rig count over this time period, but the downward slope is undeniable. Notice how the slope for new wells has continued down even as the rig count has largely flat-lined from mid-22. Next note how the rate of DUC withdrawal began to decline in January from over 200 to just 14 in the most recent report.

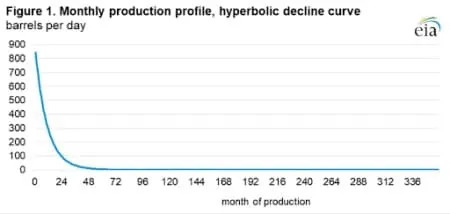

As the Initial Production over the first month-IP-30, of shale wells is relatively high, followed by a rapid decline over the first year, the oldest of these DUC’s are in their final third of productive life and will soon enter terminal decline. If nothing changes, there is a box-canyon “cliff” in shale production coming from key producing basins and especially the Permian.

The Permian is our most prolific oil play due to its wide geographical area and the multiple horizons, primarily the First, Second, and Third Bone Spring, and the Wolfcamp A, B, C, and D that can be tapped in a multilateral well. The graph below taken from the EIA-Wolfcamp report shows the vertical alignment of these individual reservoirs in their respective sub-basins, the Delaware Basin, the Central Basin Platform, and the Midland Basin.

The Permian today is producing about half the liquids, and 25% NGL’s and 25% of the natural gas that comes out of the lower 48. To say it is indispensable to U.S. energy security is an understatement. Much of our entire marginal oil supply (the amount that could be raised or lowered depending on drilling activity) comes from this play, and increasingly it is beginning to look as though its best days are in the rearview mirror, in terms of top-tier productivity.

What we haven’t seen up to this point are any signs of shale output reaching “terminal velocity” in oil company filings. In quarterly calls, the talk has all been about controlling CAPEX to maintain output at just above the rate of natural decline, or in some cases single-digit growth. And then Pioneer Natural Resources, (NYSE:PXD) announced its third quarter production and earning numbers last week. It was the equivalent of a ripple felt in the “Force.”

It was largely a good report that delivered most of what the analysts wanted to hear, particularly on PXD’s best-in-class dividend payout of $5.71 per share in base and variable components for Q-4, 2022. When management got to slide 11, of the analyst presentation, they attempted to put “lipstick on a pig,” as noted in the slide below, describing the “deferral of delayed targets.”

Rich Dealy, President of PXD commented in regard to an analyst- Doug Leggate of Bank of America, a question about this deferral.

RELATED: Oil Production At Pre-Pandemic High

“Yeah, I’d say the delayed targets have underperformed where we would have anticipated. They still have great returns. It is just we have better locations in our portfolio. And so as we’ve gotten those results over the course of this year, we’ve decided that that’s not satisfactory to us, and we want to move forward with the higher thresholds. And so we’ve just reshuffled the deck, as I said earlier, and are moving to full stack basically across the field.”

During the extreme low price era of 2020-21, operators such as PXD drilled some of their top tier acreage to maintain output and get optimal payouts for their wells. As prices began to rise companies shifted their focus to lower tier wells as the high prices enabled meeting corporate IRR and DROI (Internal Rate of Return, and Discounted Return on Investment) metrics while saving higher tier acreage for the next downturn.

This shift by PXD was an acknowledgment that this strategy was falling short in production and a pivot to the higher tier wells and extending the lateral length to 15,000 feet was necessary to maintain production output. This led to further questions on this metric from the analyst cadre.

Charles Meade of Johnson Rice, asked, “If the changes were to reverse changes made in 2022 from 2021,” or if there was “another dimension to the evolution?” In other words, do you have a clue what you are doing?

To which Dealy replied, “Yes, Charles, I’d say it’s more about just the allocation of capital and moving to higher return locations and areas. And so the returns that we are generating from the program in 2022 are still fantastic. I mean, so I don’t want anybody to take away that they’re not great returns. It’s just that productivity came in a little less than we anticipated and we wanted to rectify that and fix that and we weren’t satisfied with it. And so we’ve got a depth of portfolio that we can move things around. And so we’ve made those changes.” A bit of a word salad that seemed to satisfy Meade.

Summary thoughts and your takeaway

We now have both analytical and documented evidence of the maturing and slow decline of shale output from diminished reservoir quality. That has implications for the industry and for the commodity. Certainly, PXD is not the only company experiencing limits to growth. Drillers will become hard-pressed to maintain production output through technology, well spacing, or even sheer numbers.

This doesn’t necessarily portend a decline in revenues or profits for these companies. Conversely, it could actually drive them higher as realizations improve from increased global competition for scarce supplies.

It is also worth pointing out that even with the adjustment that PXD is making to increase production output over the short term, they have years of top-tier drilling inventory banked.

It is also worth pointing out that as these top-tier locations are consumed through Full Stack and extended reach drilling to 15,000’ the estimate in the slide above may prove to be optimistic. Time will tell on that score.

One final outcome of this decline in acreage quality may be a continuation of the aggregation of small or private producers by larger public companies. An example of this would be Devon Energy, snapping up bolt-on acreage in the Williston and Eagle Ford plays this year. My prediction is for more of the same in 2023 as companies look to ensure their long-term viability.

By David Messler for Oilprice.com

Read this article on OilPrice.com