(Bloomberg) — Oil producers in the Permian Basin and elsewhere could soon find themselves facing the oilfield equivalent of trying to walk up the down escalator.

The oil industry, and particularly the Permian, is in the midst of a boom. But analysts say new hints that maturing wells are falling well short of projections are prompting fresh worries that the industry may not be able to meet robust demand moving forward.

It’s a concern that could add new strength to an oil ally that’s been building since January, largely driven by volatile geopolitical issues. A study by Wood Mackenzie Ltd. found maturing wells in some parts of the Permian’s Wolfcamp shale were losing almost 15 percent of output annually five years after startup. That compares with the 5 percent to 10 percent initially modeled.

“If you were expecting a well to hit the normal 6 or 8 percent after five years, and you start seeing a 12 percent decline, this becomes more of a reserves issue than an economics issue.,” said R.T. Dukes, a director at industry consultant Wood Mackenzie Ltd. It means “you have to grow activity year over year, or it gets harder and harder to offset declines.”

Globally, Wood Mackenzie has predicted annual decline rates offshore will rise to 6 percent from 2020, from 5 percent now.

The newest hints of production shortfalls in maturing wells follows a two-year price rout that put the brakes on costly offshore drilling, and a more recent push by oil-company investors for payback over growth. While U.S. shale fields have been booming, analysts are now starting to wonder if long-term U.S. projections will hold up, offsetting decisions to hold off exploration elsewhere.

Older well declines “are a topic that oil market analysts and investors are always trying to wrestle with,” Jamie Webster, a senior director for oil at the Boston Consulting Group Inc. in New York, said by telephone. “It’s hard to get a good sense of it because of a lack of good, real time data. But my sense is that they are starting to increase.”

The Permian Basin “has had an amazing year, ” he added. “But it’s really started to slow down.”

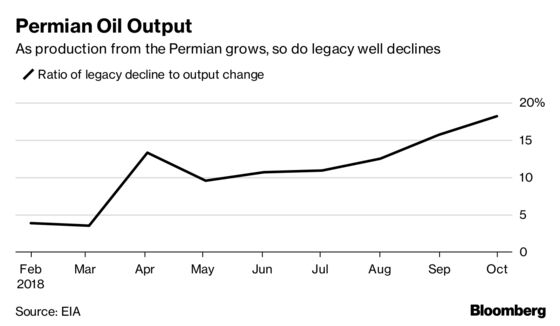

Growth in the Permian has, in fact, been shrinking, down almost every month this year, while declines in older wells are trending higher, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration. In October, the organization’s data shows declines offsetting output by about 18 percent, compared with 4 percent at the start of the year.

The concerns, though, go beyond the Permian.

Perhaps the best example of declining production in older wells comes from Brazil’s Campos basin, which has been producing oil for more than 30 years. The region, which is traditionally responsible for more than 80 percent of the nation’s oil, has seen a 30 percent decline in output over just the last five years, the country’s oil regulator said last month.

In response, Petroleo Brasileiro SA, the country’s state-controlled energy company, will be redirecting investment into new drilling in the region.

“Decline rates are dramatic and there is a lot to be done,” said Marcelo Castilho, at the sidelines of the Rio Oil & Gas Conference last month.

But there’s more to track than just the big producers, said Boston Consulting’s Webster.

While production declines being seen in smaller countries such as Turkey and Pakistan may not have a lot of immediate impact, “as a whole, the result could be quite stunning. ”

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.