Jordan Blum, Houston Chronicle — ST. FRANCISVILLE, La. — A row of pink azaleas and centuries-old live oaks lead to the Catalpa Plantation cottage here, where Mary Thompson, the fifth generation of her family to own the property, frets about its future.

In historical terms, the plantation is invaluable. But what’s underneath can be priced to sell. That’s why Thompson, a retired schoolteacher managing a 19th-century property in dire need of repairs, turned to an unlikely source of money — a lease with the Houston oil company EOG Resources to drill on her 60 acres sitting above the crude-bearing Austin Chalk formation.

“There are so many things I want to do here with renovations that I’ve always joked if I win the lottery or get an oil well, I can do it,” Thompson said. “I never buy a lottery ticket, and I had very little hope of getting an oil well, but now there’s a little slight possibility.”

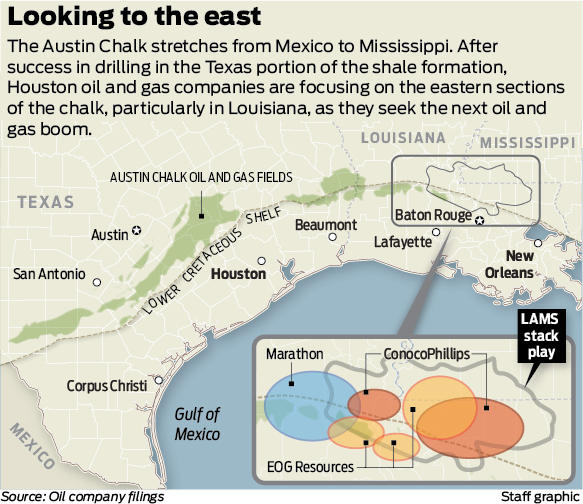

Houston oil companies such as EOG, ConocoPhillips and Marathon Oil are betting they can find oil and gas in the section of the Austin Chalk that extends deep into rural Louisiana and Mississippi. With South Texas’ Eagle Ford shale aging and West Texas’ thriving Permian Basin increasingly dominated by supermajors such as Exxon Mobil and Chevron, Houston’s top operators are exploring the Louisiana chalk as they seek the next big find in the nation’s shale revolution.

EOG, ConocoPhillips and Marathon have each leased more than 200,000 acres in Louisiana at about $1,000 an acre — compared to $100,000 an acre in parts of the Permian — and begun drilling exploratory test wells.

But introducing drilling rigs and fracking crews to a forested, flood-prone region known for plantations and historic preservation is different than pumping oil in flat and arid West Texas. Oil executives, local politicians and residents hope oil and gas development can walk a fine line of generating economic prosperity without greatly upsetting the area’s natural beauty and tourism industry.

Drilling commences on the Erwin #1 well site on Tuesday, April 2, 2019, in St. Francisville, La. The Austin Chalk shale play that stretches from Texas into Louisiana is potentially being seen as a next big oil and gas play for Houston energy companies. Photo: Brett Coomer, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

“Well, I wouldn’t say we’re prepared for it,” said Kenny Havard, president of the West Feliciana Parish where EOG and ConocoPhillips have leased land and where Thompson’s property rests. “But the oil and gas industry can be a huge boon to these communities if managed right and done correctly. It’s a delicate balance and a unique place, but we’re going to figure it out.”

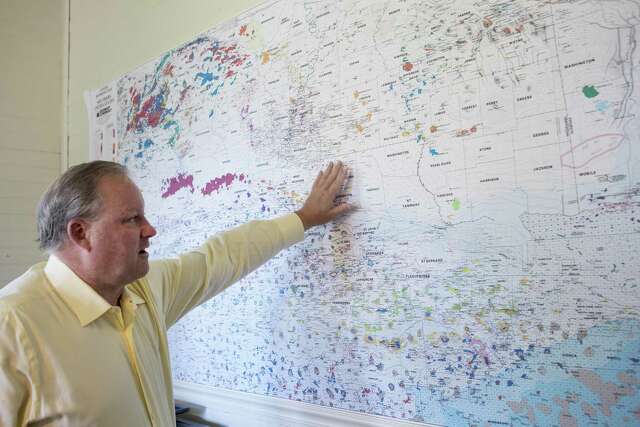

Arguably the biggest evangelist for the Austin Chalk’s oil potential in Louisiana is Kirk Barrell, president of New Orleans energy company Amelia Resources, which sells contiguous acreage in “shrink-wrap packages,” connecting the landowners with ConocoPhillips and other developers. Barrell, a former oil company geologist, has studied the Austin Chalk in Louisiana and Texas for nearly 30 years.

“We have a lot of rock that looks like the Texas rock. And these companies are bringing a lot of geologic and operational expertise to this project from Texas,” Barrell said. “Our hope is that we can see the success of South Texas’ Eagle Ford here in Louisiana.”

Kirk Barrell, president, Amelia Resources, points out the lack of drilling sites in the West Feliciana Parish area in his office on Tuesday, April 2, 2019, in St. Francisville, La. The Austin Chalk shale play that stretches from Texas into Louisiana is potentially being seen as a next big oil and gas play for Houston energy companies. Photo: Brett Coomer, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Nearly a century of chalk

The Austin Chalk stretches from Mexico to Mississippi, a limestone formation that has been drilled, mostly in Texas, with varying degrees of success for nearly 90 years.

Most of that success has come in recent years in South Texas, where the chalk rests above the Eagle Ford shale. EOG, ConocoPhillips and Marathon have all tapped the Eagle Ford and Austin Chalk in Texas, and now they see huge potential in bringing modern drilling and hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, techniques to Louisiana.

“We’re fortunate to have productive Austin Chalk in some of our Eagle Ford acreage, and we’re exploiting that,” ConocoPhillips CEO Ryan Lance said in a recent interview. “We’re going after that and learning from it so we can apply those learnings to what we have in Louisiana.”

The Austin Chalk first started producing oil in Texas in the 1930s. Apart from some modest efforts in past decades, the Louisiana chalk never attracted much interest until the shale drilling boom that began about a decade ago. Companies targeted the Tuscaloosa Marine Shale, which lies beneath the chalk but, just as they achieved mild success, oil prices collapsed in late 2014.

“The Austin Chalk has broken many hearts and bank accounts since the 1930s,” Barrell said. “But that was before modern fracking. I call this Austin Chalk 3.0. It potentially could work across the entire state of Louisiana and into Mississippi. This could be a game changer.”

EOG Resources, which pioneered the development of the Eagle Ford, jumpstarted new exploration in the Louisiana chalk by quietly drilling the Eagles Ranch 14H-1 well in Avoyelles Parish more than 18 months ago. That helped to trigger a land rush, said Patrick Courreges, spokesman for the Louisiana Department of Natural Resources. EOG just permitted in April to next drill farther east in East Feliciana Parish.

EOG has taken positions throughout the Louisiana chalk and even into Mississippi. Marathon is focused just west of the Mississippi River and ConocoPhillips to the east and largely north of Baton Rouge. Other companies have gobbled up acreage as well, including the Norwegian energy company, Equinor.

Marathon is collecting seismic imaging to map out where it aims to target its drilling, said CEO Lee Tillman. The company is proceeding slowly and patiently, Tillman said, but he is admittedly eager to see results.

“We think there are good indications that the potential can be quite broad in the Austin Chalk,” Tillman said. “But we have to prove it.”

Trucks travel to and from the Erwin #1 well site on Tuesday, April 2, 2019, in St. Francisville, La. The Austin Chalk shale play that stretches from Texas into Louisiana is potentially being seen as a next big oil and gas play for Houston energy companies. Photo: Brett Coomer, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Louisiana’s Florida

While oil and gas companies have thrived in the Permian, the Eagle Ford and other Texas shale plays, the energy industry of the state’s poorer and smaller neighbor to the east has been relegated largely to offshore oil fields, which are only beginning to recover from the oil bust that ended about three years ago.

Natural gas in the Haynesville shale, which straddles the Texas-Louisiana border, spurred a rush to northwestern Louisiana a decade ago, but the boomlet was snuffed out after natural gas prices plunged. While the Haynesville has bounced back somewhat, the southern half of the state missed out almost entirely on the shale revolution — until, perhaps, now.

Much of ConocoPhillips’ and EOG’s focus is in Louisiana’s Florida Parishes east of the Mississippi River, including West and East Feliciana parishes. The region was settled in the late 1700s and ruled by Spain as part of Florida.

The area became the focus of a territorial dispute after the Louisiana Purchase in 1803. People still wave the single-star flag of the short-lived Republic of West Florida, which declared its independence from Spain in 1810 and subsequently surrendered to the United States. In West Feliciana’s parish seat, St. Francisville, many of the homes have plaques to designate their 19th-century historic status.

“We’re the town that fought off a Walmart,” said Helen Williams, museum director at the West Feliciana Historical Society. “We don’t do change well.”

Residents say the oil and gas potential is the talk of the town, already creating haves and have nots — those who have cashed in with oil leases and those who weren’t approached or don’t own much property.

One of the biggest financial windfalls went to Herbert Erwin, who leased out almost 500 acres outside of St. Francisville to ConocoPhillips on land his father acquired in the 1930s. Erwin’s property is home to one of the first three test wells that ConocoPhillips drilled in April. He’s already received $500,000 from the lease and the well, which required cutting dozens of trees. If the well proves a success, his royalties should easily make him a millionaire.

“It’s been a blessing. It was out of the blue,” Erwin said, standing beyond a drilling site just a few hundred feet from his home. “I’m shocked that we even got a well. Hopefully, this is the first of many.”

Landowner Mary Thompson sits on the front porch at Catalpa Plantation on Tuesday, April 2, 2019, in St. Francisville, La. Thompson has leased her land to an oil company for drilling and exploration. The Austin Chalk shale play that stretches from Texas into Louisiana is potentially being seen as a next big oil and gas play for Houston energy companies. Photo: Brett Coomer, Houston Chronicle / Staff photographer

Seeking the next big thing

As companies look for the next big thing, arguably the two top prospects are the Louisiana Austin Chalk and the Powder River Basin in Wyoming, said Sarp Ozkan, director of energy analytics at the Austin research firm Drillinginfo.

While the Powder River Basin could have greater overall potential, Louisiana has the advantage of its Gulf Coast location near refining and export hubs. But, with investors focusing on bigger returns available in established oil fields such as the Permian Basin, it may take take another five years before drilling becomes widespread in the Louisiana chalk — if it ever does.

In much of the region, the chalk and Tuscaloosa Marine Shale are separated by less than 1,000 feet of depth, opening the possibility that companies could tap both formations in what’s known as a stacked play.

Mary Thompson doesn’t claim to be an expert on any of that. She only knows the oil lease money paid for her to replace the heating and air-conditioning units at the plantation. And she just prays EOG keeps its distance from her home and the oak trees.

“It is a balance. I would be upset — as much as I’d love to get an oil well — if they put one in the middle of my oak alley,” Thompson said. “I will just try to reason with them if they ever try to do it too close to me.”

—————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————-

jordan.blum@chron.com