- In the past decade, U.S. oil production has grown dramatically, leapfrogging Saudi Arabia and Russia, but with that quick growth came a lack of financial discipline.

- The U.S. energy sector is at an inflection point, with more mergers and bankruptcies expected before the industry becomes attractive to investors.

- The upstart drillers that drove hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” technology are being disrupted themselves with leadership shifting to oil majors, such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, and large independent drillers.

Patti Domm – CNBC -The U.S. oil industry shook up the world energy order in the last decade, and now it has been going through a shakeout of its own that is expected to end in more bankruptcies and mergers.

In the early part of this century, an upstart band of U.S. energy producers brought hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” technology to the world. It was an American-born innovation that helped turn the U.S. from the world’s biggest importer of oil into, just recently, a net exporter of oil and fuel products.

In the last decade, U.S. oil production boomed as producers used hydraulic fracturing and evolving horizontal drilling technology to extract oil from difficult-to-access places and some fields that had previously been considered nearly tapped out. The U.S. is now producing just under 13 million barrels a day and has become the world’s largest oil producer.

With their growing success, American drillers were able to find ready debt financing as investors were willing to gamble on the idea that wells could start producing in a fraction of the time it took more conventional drillers. That helped drive an oil glut, and global prices suffered from oversupply. The imbalance is improving, but now there are questions about how fast demand will grow.

Investors have lost patience with the industry’s boom-to-bust cycles. As a result, energy stocks have been among the worst performers of the decade, up just 4%, and energy debt is among the least desirable.

“There’s going to be a hatchet taken to these companies in the next year,” said John Kilduff, partner with Again Capital. “There will be bankruptcies and consolidation. The party is over.”

Market disruption

The growth of U.S. shale created a boom-town atmosphere in the places where drilling was growing most — West Texas and North Dakota. But it also disrupted the entire world oil market.

In what would have been unheard of a decade ago, Saudi Arabia and OPEC forged a deal with Russia and other non-OPEC producers to control their production to support oil prices. The recent extension of this three-year-old pact has helped steady prices.

Unlike many of those producers, the U.S. industry is untethered, with no government deciding production levels, and its only constraints are economic and financial. That has made life hard for U.S. drillers this year, with oil prices below their break-even level much of the year. West Texas Intermediate crude futures were at $60.81 per barrel Tuesday.

“We’re at the early stages [of the shakeout]. The problem is some of these companies still have a bit of rope to go,” said Ken Monaghan, Amundi Pioneer co-director of high yield. “They don’t have [debt] maturities that are coming up in 2020 and 2021. They’re going to try to outrun the clock and hope that oil prices move higher.”

Daniel Yergin, who has authored books on the evolution of the oil industry, said the U.S. industry is likely to morph now, as the industry hits an inflection point. The oil majors, such as ExxonMobil and Chevron, were slow to join the shale boom. But now they and the biggest oil independents will increasingly dominate the industry over the core of small independents and mom-and-pop oil drillers that launched the industry.

Both Exxon and Chevron have announced aggressive expansion plans for the Permian Basin, the hottest shale play covering a 75,000-square-mile area that runs through West Texas and southeastern New Mexico.

“It’s clearly a new era for shale. The irony is the U.S. is heading for these unimagined levels of production,” said Yergin, vice chairman of IHS Markit. “The U.S. industry is the world’s No. 1 oil producer, and it’s a major exporter, but the financial markets are giving them no credit for that anymore. The stocks were actually more highly valued when the oil price was in collapse than they are now. … Investors and producers have to work out a new social contract.”

The market-imposed discipline on energy companies is not new, but analysts see it taking a new turn, with more mergers and more debt restructurings needed for the industry to emerge in healthier shape.

“Most people are saying we don’t want you to spend money on growth. We want you to give the money back because you guys are dummies,” said Michael Bradley, energy strategist with Tudor, Pickering, Holt. “People want a return on capital. [Oil] prices today are higher than they were a year ago at this time, but cap ex is lower.”

With the new discipline is coming slower production growth. Analysts said part of the reason U.S. production has grown so quickly is that the payback on shale wells is much faster than conventional wells and, particularly, offshore platforms where development can take years.

According to Citigroup energy analyst Eric Lee, U.S. oil production’s rapid growth ramped up to 2 million barrels a day year over year in August alone. In the past week, oil production totaled 12.8 million barrels a day, up 1.2 million barrels from a year ago, according to weekly government data.

Over the past 10 years, U.S. oil production more than doubled, rising by more than 7 million barrels a day since January 2010, when it was just 5.4 million barrels per day.

“That’s what they’ve wildly been doing for the last 10 years,” said Lee. “The first crash happened because the world didn’t need as much as was being produced.” As more U.S. oil came onto the world market, oil prices fell hard in 2014 and then bottomed in 2016, at under $30 a barrel.

Lee said Citi analysts expect U.S. oil production to reach nearly 16 million barrels of crude by 2023. Analysts say the price of oil will be a big determinant in how quickly U.S. output will grow and at what level it will peak.

Mergers and a debt bomb

Energy has been the worst-performing sector in the stock market this year, as well as in the high-yield debt market.

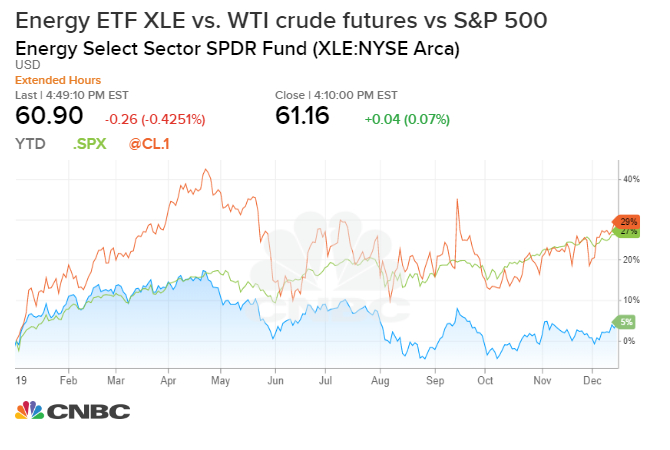

For the year to date, the XLE, the Energy Select Sector SPDR ETF, is up just 5%, compared with the 29% gain in West Texas Intermediate crude futures and the 27% gain in the S&P 500.

The energy index of the high-yield market has a face value of $170 billion and a market value of $150 billion, according to Amundi.

“There’s more distressed energy names than there are in any other sector,” said Monaghan. “Up until this month, energy bonds in the high yield index had lost money for the year-to-date, and now they’re in positive territory only in the month of December because there’s been a little higher [oil] prices.”

Bradley said he expects that about $30 billion to $40 billion of high-yield energy debt is at risk. He and other analysts said some companies will have no choice but to seek bankruptcy protection and restructure.

“Weatherford went through bankruptcy,” said Bradley. “They’re coming through it. That’s the right thing to do.”

Once the fourth-largest oil services company, Weatherford emerged from bankruptcy on Friday after selling $6 billion in assets and receiving $10 billion in support from bondholders, according to the Houston Chronicle. Those bondholders now control 94% of the company.

Some companies remain poorly capitalized, and the very nature of shale is one of the reasons.

The shale industry needs to keep drilling to keep its production rate high because of the rapid depletion of its wells in the first year alone. According to IHS, young shale wells can decline at a rate of about 70% to 75% in the first year, so companies continue to drill more wells. If they stopped drilling, production would be down by as much as 35% a year later, according to IHS.

“If you look at the problem with the sector itself, which is the significant depletion of the reserve over a briefer time than used to be the norm, you better have capital and balance sheet structures that better match that probability,” Monaghan said.

Some of these issues could be fixed in mergers, which have challenges of their own. “It’s often hard to create a merger when you have two companies or three companies that are in the walking wounded category,” said Monaghan.

“The issue then becomes the acquisition currency. It’s not easy to execute on. Then you have a management team that’s probably hoping and praying oil prices will move a little higher.”

Bradley said the merger this week between WPX Energy and private company Felix may be a sign of things to come for the sector, since Felix did not garner much of a premium. WPX shares gained after the transaction was announced and were up 16% on the week.

“This is the first deal I’ve seen in a long time where the stock was up,” said Bradley.

He expects to see more mergers in the mid-cap sector. “Anything between $2 [billion and] $7 billion is going, in the next two years, to be gobbled up,” Bradley said. He said companies such as Concho Resources and Diamondback Energy could be the larger independents, which he says would have a market cap of about $15 billion to $25 billion.

Bradley said it’s clear the majors are growing market share in shale, since they have not shut down wells while others have.

Lee said the majors now make up about 15% of shale production and are growing. “There’s still a lot of little guys,” said Lee. He said private companies continue to be a big chunk of Permian production, with about 45%.

Ultimately, analysts expect the industry to end up in better financial shape.

“Theoretically, this doesn’t bode well for the consumer,” said Kilduff. “Consolidation and mergers should bring in a much higher level of production discipline, which should mean less supply for the market and higher prices.”